First of all, love our Children

Among the million things to remember about children is that:

1. They need you because they’re vulnerable.

In the early years, especially before the age of seven, a child borrows your calm, your rhythm, your sense of safety. You are not merely a caregiver but the emotional architecture upon which they learn to self-regulate and trust the world.

Every tone of your voice, every patient pause, every boundary held with kindness becomes part of their internal compass, the very one they’ll use long after they’ve outgrown your hand.

2. No matter what kind of kid you’ve got, you love them.

Effective Strategies for Children

I wish I could tell you there’s a sure way to raise children.

You’re in luck 🙂

there are at least a few things we can try. ♥

Effective Strategies for Children

B.F. Skinner: as wonderful as they come

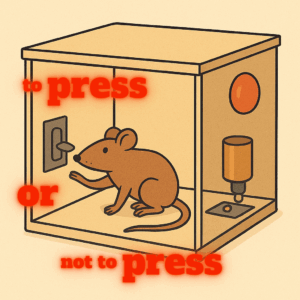

When working with children, one of the first names that often pops up is B.F. Skinner. You might’ve heard of the famous Skinner Box — made even more famous (and a bit scandalous) by Lauren Slater — though later clarified by Skinner’s own daughter, Deborah Skinner, who proved most of it to be nonsense.

The truth is, some people are brilliant researchers, others are better practitioners…

and once in a blue moon, you find someone who’s both.

When it comes to parenting, though, you have to be both — scientist and artist.

To really appreciate Skinner, you should also know a bit about the ones who came before him: Pavlov, Watson, and Thorndike.

-

Pavlov, the one with the dogs — remember? The bell rings, and the dogs salivate. That’s classical conditioning at work.

-

Watson said we should focus on observable behaviour, not guesswork about what’s going on in someone’s mind (a fair warning for overthinking your child’s every silence).

-

Thorndike, with his “Law of Effect,” showed how behaviours followed by satisfying outcomes are more likely to happen again.

Skinner wrapped all of their brilliance into something truly practical. He built a system which could be used in early education and intervention.

#radicalbehaviourism

Operant conditioning

Skinner’s most famous idea — Operant Conditioning — is the notion that behaviour is shaped by its consequences.

We learn through reinforcement (positive or negative), punishment (again, positive or negative), and sometimes, extinction (when behaviour fades because it’s no longer rewarded).

Well, behaviour engineering might sound a bit clinical, and it’s fair to ask if we’re raising mindful humans or well-trained robots. But at the heart of Skinner’s thinking lies a simple, mischievous truth:

we do what works.

It’s not just rats pressing levers; it’s us checking our phones for that little ding of validation.

Same principle — different cage.

Sound familiar?

The subtle art of reinforcement

Skinner’s schedules of reinforcement took this further, showing that timing and frequency matter more than we think. A reward that comes unpredictably, ie : a compliment, a “like,” or a bit of luck, is far more addictive than one we can set our clocks by. That’s the hidden magic of operant conditioning: life doesn’t just teach us; it trains us beautifully, sometimes ruthlessly.

Words as behaviour

Verbal behaviour is rather Skinner’s brave leap into the territory of language. He believed words themselves are learned through reinforcement. Every phrase, joke, or whisper shaped by what the world rewards us for saying. It’s a bit like jazz: we improvise, but always in tune with the environment.

Some folks find that view mechanical, even bleak, but I find it oddly comforting.

Skinner didn’t deny free will; he just reminded us that our choices grow out of patterns we can understand and change. As he once put it,

“The real problem is not whether machines think, but whether men do.”

The Poet of Cause and Effect

B.F. Skinner doesn’t always get the love he deserves. People still picture behaviourists as cold scientists pressing levers and handing out pellets. But the truth?

Skinner was less a lab tyrant and more a poet of cause and effect.

He saw life as a grand orchestra of actions and consequences: each note shaped by the rhythms of reinforcement.

And maybe that’s his true gift:

Not reducing us to behaviours, but helping us notice the strings —

so that, at last, we might learn how to dance.